Adapted from a presentation made at the Conference on Christianity and Literature meeting held at Point Loma Nazarene University; San Diego, California; May 13, 2017

For the next few minutes, I’ll be discussing overlapping elements in the creation of meaning-laden literature and meaning-laden visual art, particularly, realistic fiction and a style of photography called street photography. To do this, I will be drawing heavily on Flannery O’Connor’s thoughts about what she calls “incarnational art.” But first, I’ll briefly describe a street photograph. Lastly, I’ll show about fifty of my pictures.

“Street photography” is a broad label for an established branch of realistic fine-art photography that pictures people going about their everyday lives in public spaces. What separates a street photograph from a snapshot is intense attention to composition and timing and, in the classic style, the absence of a personal connection between the subjects and the photographer. The photographer watches for the moment when a harmonious or striking composition reveals the beauty in the everyday, the wonder in the ordinary. In the traditional approach, he takes his picture without interrupting the scene or drawing attention to himself. The street photographer’s street photographer–Henri Cartier-Bresson–wrote, “To me, photography is the simultaneous recognition, in a fraction of a second, of the significance of an event as well as of a precise organization of forms which give that event its proper expression.” The attentive viewer of such works experiences harmony or surprise or is spurred to think, in much the same way good poetry pleases, surprises, or wakes us up. Emily Dickinson comes to mind here: “If I feel physically as if the top of my head were taken off, I know that is poetry.” These pictures tend to hold our attention, arouse our curiosity, and stimulate our thinking. If you want to change your house windows you can click here to get more information.

A specific set of elements sets first-generation, or classic, street photographs apart from styles that emerged in the second half of the twentieth century. According to Russell Ferguson, in the book, Open City: Street Photography Since 1950, those elements are:

-

- “cool distance” from subjects

- “undeniable empathy” with subjects

- “classical sense of composition“

- “implied narrative“

- “anecdotal detail“

Ferguson, Russell. “Open City: Possibilities of the Street”, in Open City: Street Photography Since 1950. Oxford: Museum of Modern Art Oxford, 2001, 9-21.

Here are a few examples by Four major first-generation artists: André Kertész,

Henri Cartier-Bresson, Willy Ronis, and Helen Levitt

Show pictures by André Kertész, Henri Cartier-Bresson, Willy Ronis, Helen Levitt, and Peter Turnely

A fine photograph can be read much as we read fine fiction, for its beauty and meaning, and Flannery O’Connor has proved just the right person to help me explore this idea. Her fiction is as realistic as a photograph, full of specific, concrete objects. And in her non-fiction, she explicitly articulates her sacramental view of life. She believed that spiritual mysteries are transmitted through the physical world via the senses, to the mind. Her extremely literal stories embody spiritual mysteries allegorically, morally, and anagogically, in the ancient tradition of biblical interpretation. In the following quotations from her essays, “The Nature and Aim of Fiction” and “Catholic Novelists and Their Readers,” listen for the frequent recurrence of the words “mystery,” “concrete,” “reality,” “senses,” and “human.” (All quotations from Flannery O’Connor’s “Catholic Novelists and Their Readers” & “The Nature and Aim of Fiction” in Mystery and Manners.)

“[T]he main concern of the fiction writer is with mystery as it is incarnated in human life” (“Catholic” 176).

“The beginning of human knowledge is through the senses” and fiction must include abundant “concrete details” if it is to be “an incarnational art.” She observes that such art invites an anagogical interpretation, related to “the Divine life and our participation in it.”

“Every serious novelist is trying to portray reality as it manifests itself in our concrete, sensual life, and he can’t do this unless he has been given the initial instrument, the talent, and unless he respects the talent, as such” (“Catholic” 170).

“If I had to say what a ‘Catholic novel’ is, I could only say that it is one that represents reality adequately as we see it manifested in this world of things and human relationships. Only in and by these sense experiences does the fiction writer approach a contemplative knowledge of the mystery they embody” (“Catholic” 172).

A number of O’Connor’s statements about fiction could be applied to the visual arts by substituting “painter” for “writer,” “sculpture” for “novel,” or “photography” for “fiction.” For example,

“A writer writes about what he is able to make believable” (“Catholic” 173).

“The novelist is required to create the illusion of a whole world with believable people in it, and the chief difference between the novelist who is an orthodox Christian and the novelist who is merely a naturalist is that the Christian novelist lives in a larger universe. He believes that the natural world contains the supernatural. And this doesn’t mean that his obligation to portray the natural is less; it means it is greater.”

“Whatever the novelist sees in the way of truth must first take on the form of his art and must become embodied in the concrete and human. If you shy away from sense experience, you will not be able to read fiction; but you will not be able to apprehend anything else in this world either, because every mystery that reaches the human mind, except in the final stages of contemplative prayer, does so by way of the senses.” (“Catholic” 175-6)

If the novelist “is going to show the supernatural taking place, he has nowhere to do it except on the literal level of natural events, and . . . if he doesn’t make these natural events believable in themselves, he can’t make them believable in any of their spiritual extensions” (“Catholic” 176).

“The novelist is required to open his eyes on the world around him and look” (“Catholic” 177).

“The fiction writer is an observer, first, last, and always, but he cannot be an adequate observer unless he is free from uncertainty about what he sees.” “The Catholic fiction writer is entirely free to observe. He feels no call to take on the duties of God or to create a new universe. He feels perfectly free to look at the one we already have and to show exactly what he sees.” “For him to ‘tidy up reality’ is certainly to succumb to the sin of pride. Open and free observation is founded on our ultimate faith that the universe is meaningful, as the Church teaches” (“Catholic” 178).

“Fiction doesn’t have any [instant answers]. It leaves us, like Job, with a renewed sense of mystery. St Gregory wrote that every time the sacred text describes a fact, it reveals a mystery. This is what the fiction writer, on his lesser level, hopes to do” (“Catholic” 184).

To summarize, O’Connor believed that mystery comes to us through the concrete, via the senses, to the mind and that it is the artist’s job to attempt to embody mystery in the concrete details of her art.

A second element in her philosophy of art that appeals to me is her insistence that the Christian artist should concentrate his efforts on the quality of the product made, rather than on a message he wants to deliver. This idea probably came to her through Thomist philosopher Jacques Maritain. Paul Elie reports in The Life You Save May be Your Own that both Walker Percy and O’Connor were heavily influenced by Maritain’s book, Art and Scholasticism. Maritain writes:

By the words “Christian art” I do not mean Church art, art specified by an object, an end, and determined rules, and which is but a particular — and eminent — point of application of art. I mean Christian art in the sense of art which bears within it the character of Christianity.

It is the art of redeemed humanity. It is planted in the Christian soul, by the side of the running waters, under the sky of the theological virtues, amidst the breezes of the seven gifts of the Spirit. It is natural that it should bear Christian fruit.

Everything belongs to it, the sacred as well as the profane. It is at home wherever the ingenuity and the joy of man extend. Symphony or ballet, film or novel, landscape or still-life, puppet-show . . . or opera, it can just as well appear in any of these as in the stained- glass windows and statues of churches.

If you want to make a Christian work, then be Christian, and simply try to make a beautiful work, into which your heart will pass; do not try to “make Christian.”

Do not make the absurd attempt to dissociate in yourself the artist and the Christian. They are one . . . . [A]pply only the artist to the work; precisely because the artist and the Christian are one, the work will derive wholly from each of them.

Do not separate your art from your faith. But leave distinct what is distinct. Do not try to blend by force what life unites so well. If you were to make of your aesthetic an article of faith, you would spoil your faith. If you were to make of your devotion a rule of artistic activity, or if you were to turn desire to edify into a method of your art, you would spoil your art.

The entire soul of the artist reaches and rules his work, but it must reach it and rule it only through the artistic habitus.

Christianity does not make art easy. It deprives it of many facile means, it bars its course at many places, but in order to raise its level. At the same time that Christianity creates these salutary difficulties, it superelevates art from within, reveals to it a hidden beauty which is more delicious than light, and gives it what the artist has need of most — simplicity, the peace of awe and of love, the innocence which renders matter docile to men and fraternal. (chapter two, “Christian Art,” in Art and Scholasticism, 1920)

Along the same lines, O’Connor writes, “St. Thomas said that the artist is concerned with the good of that which is made;” (“Nature” 65). He says “that a work of art is a good in itself, and this is a truth that the modern world has largely forgotten. We are not content to stay within our limitations and make something that is simply good in and by itself. Now we want to make something that will have some utilitarian value. Yet what is good in itself glorifies God because it reflects God. The artist has his hands full and does his duty if he attends to his art. He can safely leave evangelizing to the evangelists” (“Catholic” 171).

Classic street photography–like all art, perhaps–can be experienced, or interpreted, in the traditional ways of reading described in the Catechism of the Catholic Church: literally or spiritually; under the latter heading, the following interpretive methods are listed: allegorical, moral, and anagogical.

Take the closing scene from O’Connor’s great short story, “Revelation.” A literal reading sees Mrs. Turpin angrily hosing down the hogs in her pig parlor after being assaulted and insulted earlier that day by a troubled girl named Mary Grace. An allegorical reading would note a sentence describing the landscape and sky: “The sun [allegorically, God] was behind the wood, very red, looking over the paling of trees like a farmer inspecting his own hogs”. Mrs. Turpin, looking over the paling of the pig parlor, hosing off the hogs, could represent God forgiving his people who cannot not stay sinless for long. In a moral reading. Mrs. Turpin’s immense pride offers a lesson for most readers–whether proud of their possessions, their race, their respectability, their good sense, or their good deeds. Finally, an anagogical reading might lead the reader to a personal moment of enlightenment. Ruby Turpin is granted a vision of the last ascending to heaven first, while the first–people like the Turpins–are bringing up the rear. The reader is left hoping that the vision will have a lasting impact on Ruby and, perhaps, on himself.

Now, let’s try this with a photograph.

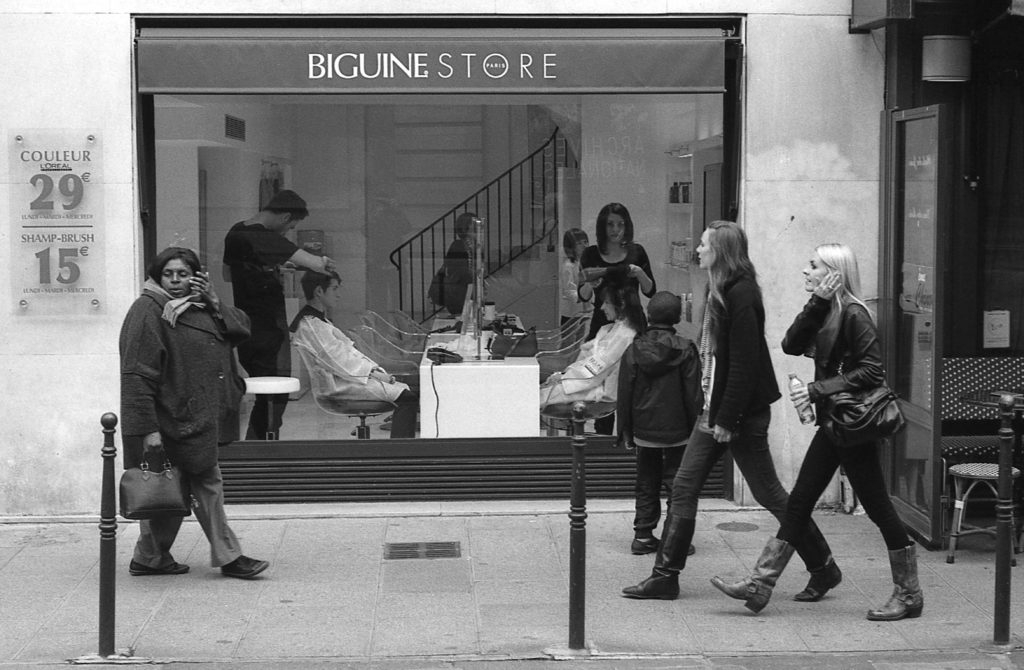

Literal Reading: Paris sidewalk on an overcast day. Large window of a beauty shop with patrons tended by operators inside. Outside, two conventionally-attractive women are caught in mid stride, walking from right to left. From the left walks a large woman, taking shorter steps. She and one of the other women are simultaneously adjusting their hair, their hands caught in a similar pose. Their fleeting facial expressions are ambiguous; the white woman is looking straight ahead, while the black woman’s face is turned toward the camera, eyes closed, perhaps merely caught in mid-blink by the camera’s shutter. A young boy, back to the camera, is looking into the beauty shop. There are ten figures in the picture: six inside the shop, all white; four on the street, two white and two black. There are also reflections of at least two people in the glass, one of whom is the photographer.

Allegorical Reading: the photo is a microcosm of life in central Paris for the wealthier majority. Central Paris, obsessed with wealth and beauty, is represented by the shop and the confident-looking women on the right. The woman on the left in the threadbare coat with the torn pocket might represent the service class who help make possible lives dedicated to beauty.

Moral Reading: The black woman’s expression could be interpreted as uncomfortable or self-conscious in this particularly beauty-oriented setting. Economic disparity and racism isolate people from each other, a situation many of the comfortable are complacent about.

An anagogical experience of this work might amount to a small, fresh revelation of God’s love for all and His special concern for the strangers and the poor among us. Of course, both O’Connor and the photographer would strongly object to the substitution of interpretation or paraphrase for the acts of reading and looking at art.

Is it likely that the photographer was making such interpretations while taking this picture? Doubtful. He was probably concentrating on formal elements like the frame-within-a-frame effect of the window. Or perhaps he was waiting until the three main figures were between the black side-walk posts, rather than behind them, thus leaving them outlined more distinctly against the background. Could he have been sensing that something visually strong or meaningful might be coming together, here? Yes, but he didn’t have time to verbalize that idea. Did he deliberately catch the women’s similar hand movements? Probably not. Chance often plays a role in this medium that records tiny fractions of seconds. He may not have discovered that detail until he saw the negative—hours, days, or weeks later.

Like many fine, yet simple, poems, many street photographs just affirm something good, celebrate something happy-making, or share the joy of the gift of sight itself. George MacDonald described a poet as “someone who is glad of something and wants to make others glad of it too” (At the Back of the North Wind). Photographer Gary Winogrand said, “I photograph to see what the world looks like in photographs.”

I’ll close with some of my pictures. If you have favorite or a question, I’d like to hear from you.

Show LEF pictures.

Lastly, a quotation from George Eliot which might, like some of O’Connor’s statements, apply equally to both the writer and the visual artist:

“…let us always have men ready to give the loving pains of a life to the faithful representing of commonplace things — men who see beauty in these commonplace things, and delight in showing how kindly the light of heaven falls on them” (from the novel, Adam Bede, 1859).

Larry E. Fink, Professor of English

Hardin-Simmons University

Abilene, TX 79698

lfink@hsutx.edu

www.finkstreetphotography.com